Introduction

What Is the Flexitarian Diet?

Cardiovascular Health

Weight Management and Metabolic Health

Cancer Risk Reduction

Nutrient Sufficiency Compared to Vegan Diets

Sustainability and Environmental Benefits

Flexibility as a Strength

Considerations and Challenges

Conclusions

References

A flexible approach to eating less meat is delivering big wins for heart health, weight control, cancer prevention, and the planet, without forcing you to go vegan.

Image Credit: Images Products / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Images Products / Shutterstock.com

The flexitarian diet is gaining popularity among health-conscious and environmentally aware consumers. Unlike strict vegetarian or vegan diets, flexitarianism promotes meat reduction without complete abstinence.

Over the past several decades, scientific evidence has highlighted the benefits of less meat intake, including reduced greenhouse gas emissions and a lower risk of many chronic diseases. As populations in high-income countries slowly begin to reduce animal-source foods, flexitarianism offers a practical approach for those unwilling to completely eliminate meat from their diet.1

What Is the Flexitarian Diet?

The flexitarian diet, a combination of the words “flexible” and “vegetarian,” describes a primarily plant-based eating pattern that occasionally includes meat, fish, or other animal products. Unlike strict vegetarian or vegan diets, the flexitarian diet allows for the moderate consumption of animal-based foods based on individual preferences.

A typical flexitarian diet includes whole and minimally processed foods such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and nuts, with the degree of restriction varying between individuals. For example, some individuals may exclude red meat but still consume poultry or fish, whereas others may consume all types of meat in limited amounts, such as once or twice a week.

Many people are adopting the flexitarian diet to support their health while simultaneously reducing their environmental footprint. As it does not impose strict rules, flexitarianism offers a practical and inclusive path toward healthier, more mindful eating.2

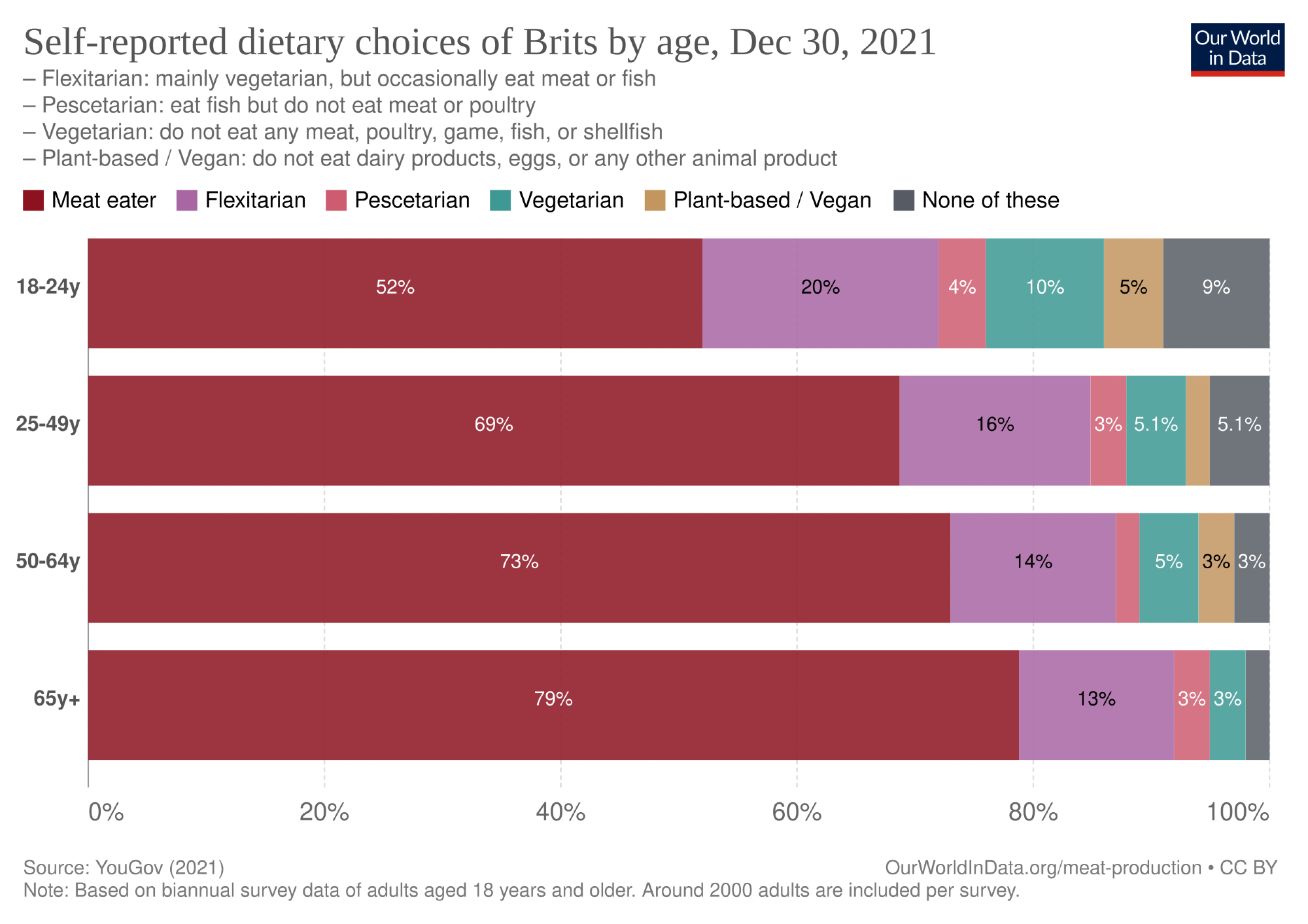

Image Credit: Edouard Mathieu and Hannah Ritchie

Image Credit: Edouard Mathieu and Hannah Ritchie

Cardiovascular Health

Several studies support the cardiovascular benefits of plant-forward diets, especially flexitarian and vegan dietary patterns. In a recent cross-sectional study in Germany comparing 94 adults following flexitarian, vegan, and omnivorous diets, both flexitarians and vegans had significantly lower total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, and insulin levels as compared to omnivores. Flexitarians also exhibited the most favorable metabolic syndrome (MetS) scores, along with reduced arterial stiffness measured through pulse wave velocity. The flexitarian diet may also reduce body fat percentages, particularly among women, while also contributing to the increased consumption of vegetables, fruits, nuts, seeds, and plant-based milk alternatives.1,3,4

Supporting evidence from a broader literature review similarly reported that semi-vegetarians who reduce meat intake multiple days every week have lower blood pressure levels and improved metabolic markers. One large cohort study also found that individuals who reduced their meat intake were less likely to develop ischemic heart disease than regular meat-eaters.1,3,4

Weight Management and Metabolic Health

Flexitarian or semi-vegetarian diets (SVDs) have been associated with positive outcomes in weight management and metabolic health.

Numerous studies have reported that individuals following flexitarian or semi-vegetarian diets (SVDs) often have lower body mass index (BMI) values and body fat as compared to non-vegetarians. Postmenopausal women consuming an SVD for over two decades also exhibited significantly lower blood glucose, insulin, and insulin resistance levels than non-vegetarian women.2

Large population studies, such as the Adventist Health Study-2 and India’s National Family Health Survey, reported a lower incidence of diabetes among those following SVDs, lacto-ovo-vegetarian, or lacto-vegetarian diets. These diets typically include high fiber intake and reduced saturated fat consumption, both of which can improve glycemic control and insulin sensitivity.

SVDs may support a healthier gut microbiome due to the fiber-rich nature of plant-based foods.

Cancer Risk Reduction

A flexitarian diet appears to be protective against several types of cancer. For example, findings from the Adventist Health Study-2 indicate that individuals following vegan diets were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with cancer, including breast and prostate cancers

Pesco-vegetarians are the least likely to develop colorectal cancer, followed by lacto-ovo vegetarians, vegans, and semi-vegetarians, thus indicating that dietary patterns focused on whole foods may reduce cancer risk. Although additional research is needed to confirm these associations and clarify the mechanisms involved in the anti-cancer effects of these dietary patterns, semi-vegetarian diets are a safe and health-enhancing approach to cancer prevention.2

Nutrient Sufficiency Compared to Vegan Diets

Flexitarian diets may also offer nutritional advantages over strict vegan diets by reducing the risk of common deficiencies associated with this more restrictive eating pattern. Research indicates that while vegan diets often fall short in nutrients like vitamin B12, iron, zinc, and omega-3 fatty acids, semi-vegetarian diets can help bridge these gaps.

For example, a cross-sectional study conducted in Austria reported significantly lower levels of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids in vegans and vegetarians as compared to semi-omnivores. Similarly, research involving over 9,000 Australian women reported that iron deficiency rates were highest in vegetarians (42.6%), followed by semi-vegetarians (38.6%), and lowest in non-vegetarians (25.5%).

Taken together, these findings suggest that the occasional inclusion of fish, eggs, or meat can enhance nutrient status. The flexibility of this diet may also improve long-term adherence as compared to more restrictive approaches.2

Sustainability and Environmental Benefits

A primarily plant-based diet can significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions, as well as the consumption of water and land resources. In fact, the exclusion of all animal-based products from an individual’s diet is associated with an 82% reduction in food-related emissions, thus highlighting the ecological potential of vegetarian and vegan diets.

Countries that integrate more plant-based options into their dietary guidelines often demonstrate stronger environmental performance. These results have led global frameworks like the EAT-Lancet Commission’s Planetary Health Diet to advocate for reduced consumption of animal products to safeguard both human health and planetary sustainability.

National food-based dietary guidelines are also increasingly encouraged to align with these principles by promoting whole grains, legumes, nuts, and a variety of fruits and vegetables, while moderating animal-based food intake. These dietary shifts are essential for achieving long-term environmental goals and supporting sustainable food systems worldwide.5,6

Flexibility as a Strength

A key strength of the flexitarian diet is its adaptability, which makes it easier for individuals to reduce their meat consumption without the rigidity of vegetarian or vegan regimens. This flexible approach allows people to gradually reduce meat intake at their own pace, thereby improving the likelihood of long-term adherence.

Fexitarian diets promote consuming a wide variety of food, which supports a more diverse and balanced nutrient intake. Unlike strict dietary plans that may feel limiting, the non-binding nature of flexitarianism empowers individuals to make choices based on personal values, preferences, and evolving health goals, leading to sustainable change over time.7

Considerations and Challenges

Although reducing meat intake is associated with numerous benefits, not all flexitarian diets are created equal, as health outcomes will vary widely depending on food choices. Prioritizing whole, nutrient-dense foods like legumes, vegetables, whole grains, and nuts is essential to avoid deficiencies.

Furthermore, to maintain a balanced intake of iron, vitamin B12, and omega-3 fatty acids, flexitarians must be intentional about dietary variety. Thus, careful planning ensures long-term health and nutritional adequacy.1

Conclusions

By emphasizing whole, nutrient-dense foods and reducing reliance on animal products and processed items, individuals can support heart health, manage weight, prevent cancer, and reduce their ecological footprint. Flexitarianism does not demand perfection, as small, consistent shifts toward eating more plants and fewer processed foods can yield measurable results.

The flexitarian diet’s adaptability makes it easier to sustain long-term, thereby offering a realistic path for people seeking to improve their health without strict restrictions.

References

- Dagevos, H. (2021). Finding flexitarians: Current studies on meat eaters and meat reducers. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 114, 530-539. DOI: 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.06.021, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924224421003952?via%3Dihub

- Derbyshire, E. J. (2017). Flexitarian diets and health: a review of the evidence-based literature. Frontiers in nutrition, 3, 231850.DOI: 10.3389/fnut.2016.00055, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/nutrition/articles/10.3389/fnut.2016.00055/full

- Bruns, A., Greupner, T., Nebl, J., & Hahn, A. (2024). Plant-based diets and cardiovascular risk factors: a comparison of flexitarians, vegans and omnivores in a cross-sectional study. BMC nutrition, 10(1), 29. DOI: 10.1186/s40795-024-00839-9, https://bmcnutr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40795-024-00839-9

- Dybvik, J. S., Svendsen, M., & Aune, D. (2023). Vegetarian and vegan diets and the risk of cardiovascular disease, ischemic heart disease and stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. European journal of nutrition, 62(1), 51-69. DOI: 10.1007/s00394-022-02942-8, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00394-022-02942-8

- Klapp, A. L., Feil, N., & Risius, A. (2022). A global analysis of national dietary guidelines on plant-based diets and substitutions for animal-based foods. Current Developments in Nutrition, 6(11), nzac144. DOI:10.1093/cdn/nzac144, https://cdn.nutrition.org/article/S2475-2991(23)00560-7/fulltext

- James-Martin, G., Baird, D.L., Hendrie, G.A., Bogard, J., Anastasiou, K., Brooker, P.G., Wiggins, B., Williams, G., Herrero, M., Lawrence, M. and Lee, A.J. (2022). Environmental sustainability in national food-based dietary guidelines: a global review. The Lancet Planetary Health, 6(12), e977-e986. DOI: 10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00246-7, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(22)00246-7/fulltext

- Strässner, A. M., & Wirth, W. (2024). Shades and shifts in flexitarian and meat-oriented consumer profiles in a German panel study. Appetite, 197, 107298. DOI: 10.1016/j.appet.2024.107298, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666324000990

Source: bing.com